Factfulness: Ten Reasons we’re wrong about the world and why things are better than you think

How I came across the book:

Through Bill Gates book blog.

Best quotes from the book:

1. Child mortality rate measures the temperature of a whole society. Like a huge thermometer.

2. Things can be both bad and better.

3. Fears that once helped keep our ancesters alive, today help keep journalists employed.

4. The math was difficult because of what I was counting. I was counting dead children.

5. It seems heartless and cruel, I know, to count dead children and to talk about cost-effectiveness in the same sentence as a dying child. But if you think about it, working out the cost-effective way of saving as many children’s lives as possible is the least heartless exercise of them all.

6. The world cannot be understood without numbers. And it cannot be understood with numbers alone.

7. Societies and cultures are not like rocks, unchanging and unchangeable. They move.

8. Give a child a hammer and everything looks like a nail.

9. A long jumper is not allowed to measure her own jumps. A problem-solving organization should not be allowed to decide what data to publish either.

10. Data must be used to tell the truth, not to call to action, no matter how noble the intentions.

Introduction:

Hans Rosling was a Swedish Professor of Global Health at Karolinska Institute. He became well-known after he gave a vivid lecture on global health trends at the TED talk in 2006 with the help of interactive bubble charts. He spent decades working in Africa as a medical officer. In the later stage of his life, he gave lectures and presentations around the world, trying to educate people against widespread ignorance. He was named as one of Time’s World’s 100 most influential people in 2012.

Summary:

Try answering these 3 questions. As of 2018,

Q1. In all low-income countries across the world today, how many girls finish primary school?

a. 20%

b. 40%

c. 60%

Q2. How many of the world’s 1-year old children today have been vaccinated against some disease?

a. 20%

b. 50%

c. 80%

Q3. Worldwide, 30 year old men have spent 10 years in school on average. How many years have women of the same age spent in school?

a. 3 years

b. 6 years

c. 9 years

The answer to all these 3 questions is ‘c’. Hans took these and other similar questions to every major conference around the world and tested audiences from all walks of life including medical students, University lecturers, eminent scientists, investment bankers, journalists, activists, political leaders, economists and policy decision makers. Every time, he was astonished at the results of these tests which were worse than random, worse than what chimpanzees would have chosen. That’s when he began realising the scale of ignorance that existed in people’s minds regarding the state of the world.

Only actively wrong knowledge can make people score so badly. He concluded that not only did people have an ‘outdated’ knowledge of the world, but it is also our natural instincts that have contributed to our persistently dramatic worldview. No one has enough mental capacity to consume all the information that is bombarded to us, and so we have an effective barrier, an ‘attention shield’ between the world and our brain, which protects us from all that noise. But it has these 10 instinct-shaped holes in it:

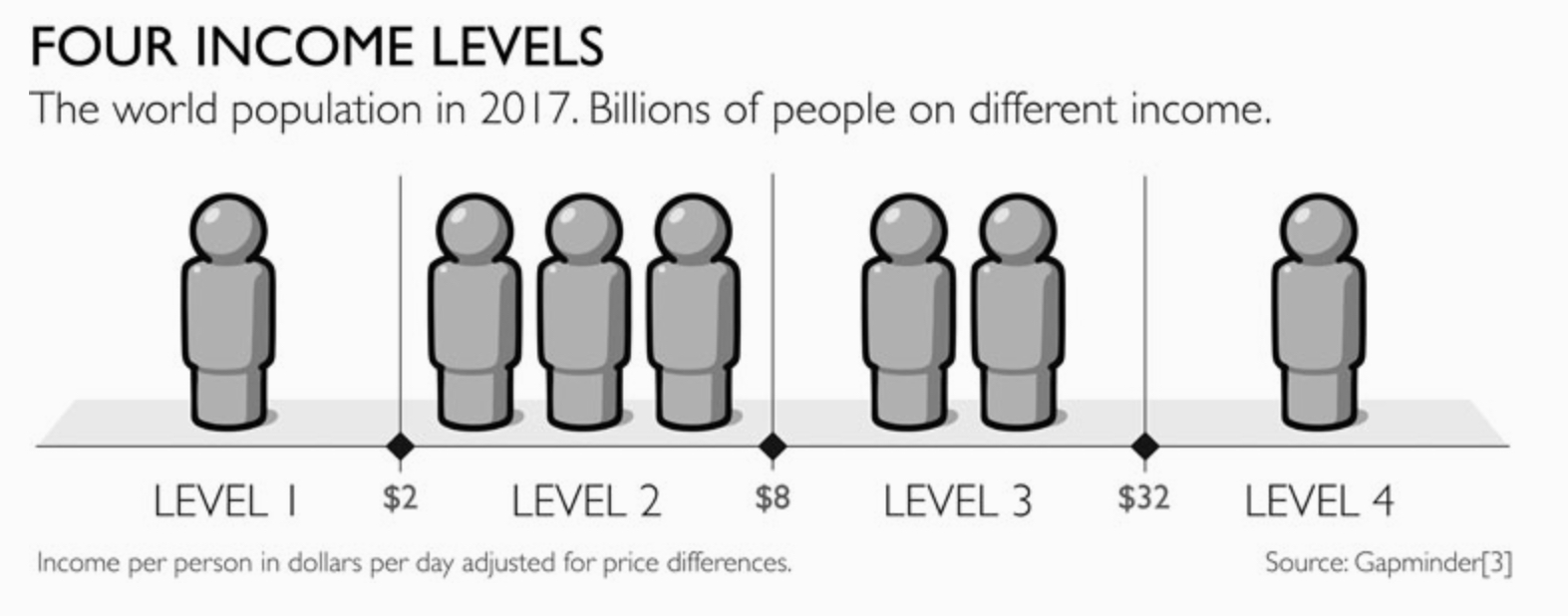

1) Gap Instinct (Look for the majority): People have a tendency to divide things into two distinct groups like rich and poor, developed and underdeveloped, good and bad, heroes and villains, west and the rest. But majority of things are in the middle. Hans says that the terms ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ are outdated, and people should rather be separated based on income levels. It’s not helpful to label countries as developing or developed, when there is a huge range of income levels within those countries.

5 billion people live in the middle as you can see. 75% of humanity lives right there where the gap is supposed to be. Looking down from the top of a skyscraper, all other buildings may look similarly short in height, but that doesn’t mean that they are equally short or short indeed.

2) Negativity Instinct (Expect bad news): It is an instinct where we notice more bad than good. Misremembering of the past and selected reporting of bad news is what’s behind this. Hans says that although many things are bad in the world, in general the world is getting better. Things can be both bad and better. He gives an example of a premature baby in an incubator. If they are still in the incubator, but all their health measures are improving – then although things are bad, it is still better.

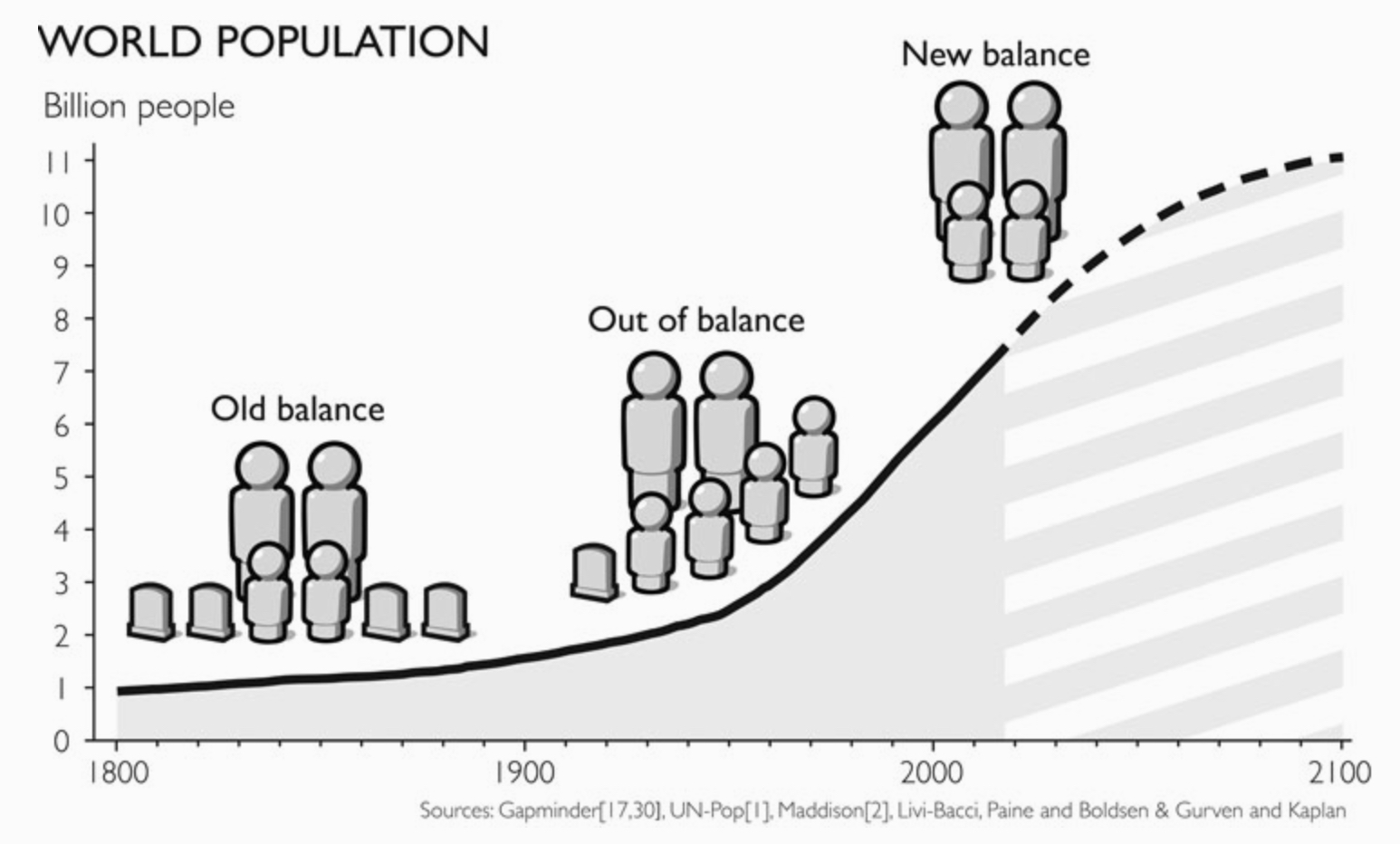

3) Straight Line Instinct (Lines might bend): People expect that population will just keep on growing in a straight line, but in statistics, curves have different shapes. For centuries, the population growth curve was flat. There was a balance. But humans rather than living, they died in balance with nature. Parents had 6-8 kids, out of which only few would survive. It was tragic. But now after a couple of centuries of sharp growth in population and global developments, there will be a new balance. This time, humans will live in balance. Parents can have 2 kids and neither of them will die.

4) Fear Instinct (Calculate the risks): Out of 40 million commercial passenger flights in the year 2017, only 10 ended in fatal accidents. It’s a remarkable feat and a great story of human progress, achieved through collaboration. In 1930s, flying was not all that safe. In 1944, at the Chicago Convention, all the commercial airlines agreed on incident reporting and learning from each other’s mistakes. Yet only those 10 flights made it to the news! Similarly, terrorism, chemophobia and many other dramatic issues appeal to our fear instincts.

5) Size Instinct (Get things in proportion): A single number on its own is often misleading. 4.2 million babies died in 2017. On its own it looks tragic, which it is. But in 1950, this number was 14.4 million. Comparisons, relative numbers or rates tell the whole story. Its also easy to get numbers and proportions wrong, but applying the 80/20 rule will generally simply things. 80% of anything is contributed by 20% of something. For eg. In 2100, 80% of the world’s population will be in Africa and Asia. PIN code of the world currently is 1-1-1-4 (1 billion each in Americas, Europe and Africa, with 4 billion in Asia). By 2100, this PIN code will be 1-1-4-5 (1 billion each in Americas and Europe, 4 billion in Africa and Asia). By 2040, 60% of Level 4 consumer market will be outside the West. African and Asian markets therefore may be the biggest economic opportunity in world history.

6) Generalization Instinct (Question your categories): Hans tells 2 wonderful stories of how we use generalization instincts. One of her students on a visit to a developing nation, had put her leg in between the elevator doors while trying to catch the lift. But unlike the elevators in rich countries, the elevator doors kept on closing tightly around her legs, until someone pressed the emergency stop button. Another instance when Hans himself was studying in Bangalore (India) as a medical student had expected himself to know much more than the students there because he was from a rich country, until he realised that his assumptions were wrong. These sweeping generalizations from their view of one world affected their judgement in these situations.

Look for differences within groups – Split people in smaller, more precise categories.

Look for similarities across groups – People from similar income levels across religions, countries and cultures have similar lives.

Look for differences across groups – What is taken granted at Level 4 or in your culture, may not be taken granted elsewhere.

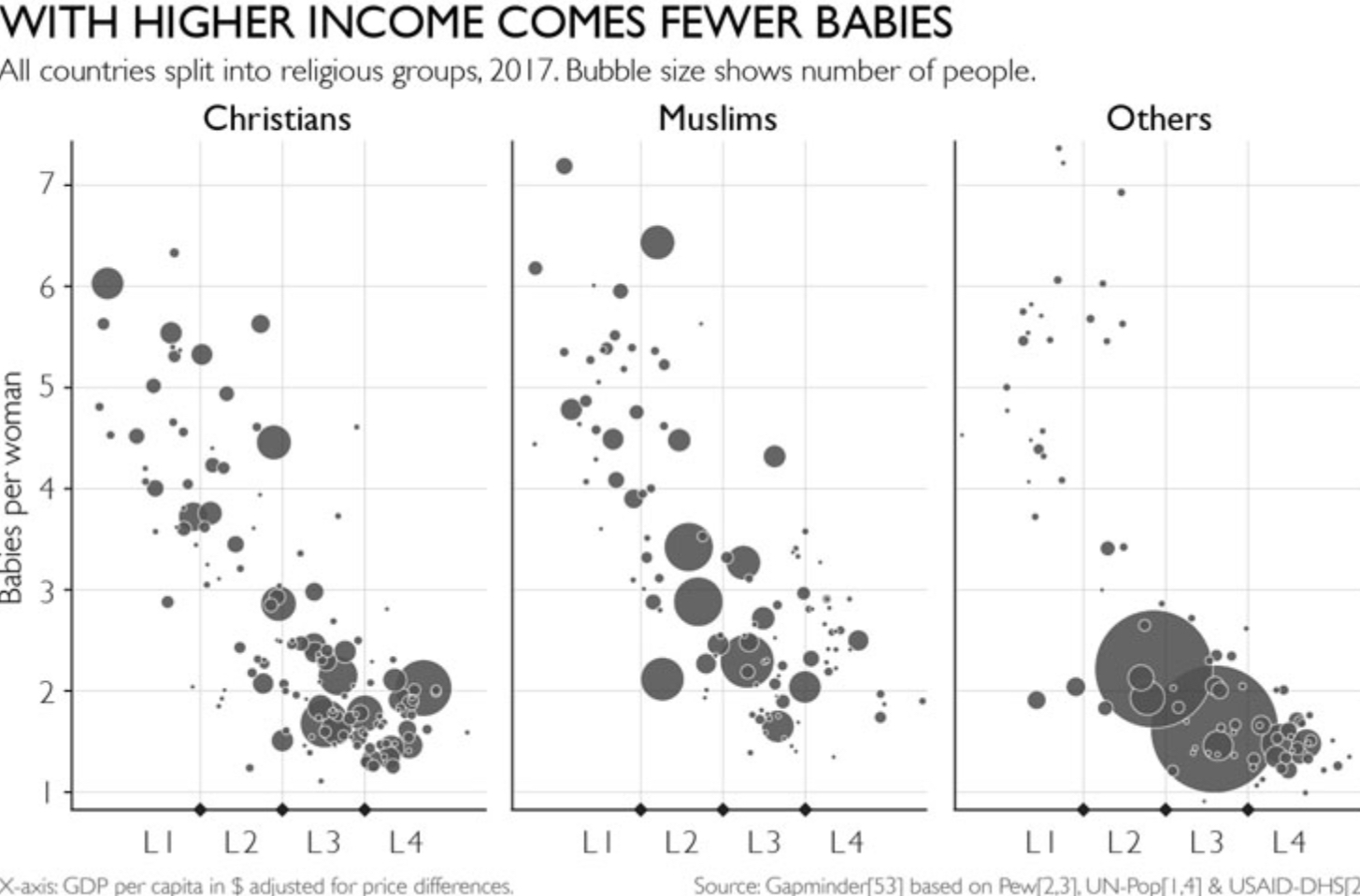

7) Destiny Instinct (Slow change is still change): People who snobbishly look down upon other races, cultures or nations believe that it is in the destiny of these groups to suffer, and that things will never change for them. But truth be told, things are always changing, or improving rather. And these changes lead to changes in culture and mentalities as well. For eg. In Iran, the number of babies/woman went down from 6 in 1984 to less than 3 only 15 years later, the fastest drop ever recorded. Iran was also the home to the biggest condom factory in the world in 1990s with compulsory pre-marriage sex education. Free media is no guarantee that these fast cultural changes in the world will be reported. Its not religion, but income that has the most direct impact on the number of babies a woman chooses to have. The number of babies/woman for Muslims in the world today is 3.2 and for Christians it’s 2.7. The difference is negligible.

8) Single perspective instinct (Get a toolbox): Understanding the world from a single perspective is like forming an opinion of someone by just looking at their foot. Problems of life are more complex than that. They need to be looked from all perspectives. Get a toolbox, not a hammer. Even democracy is not the single solution, as the 9 out of 10 countries with fastest economic growth in 2016 score low on democracy.

9) Blame instinct (Resist pointing your finger): Hans tells the story of how a small family business called Rivopharm were able to secure a UNICEF medicine contract for an unbelievably low bid, and how he had subsconsciously suspected the pharma company for fraud, only to find out later the underlying technology and business strategy that was allowing them to do business at such a low price. We often find a scapegoat when things go wrong, such as blaming refugees for economic issues or blaming lower-income higher populations nations for CO2 emissions. Its not the individuals but systems that need to be looked into. But it is also these systems in the form of institutions (invisible hard working people like plumbers, nurses, teachers, electricians, firefighters who make up these institutions) and technology, which have led the march for global development.

10) Urgency instinct (Take small steps): In the wild, the instinct to act urgently probably served our ancestors well, when faced with imminent danger. But now that we have eliminated most immediate dangers and face more complex and abstract problems, this instinct doesn’t serve us well. When we are afraid and we act in a rush, we make bad decisions. The future requires us to gather and process information, engage in dialogue, discuss and then apply analytical thinking to solve complex problems. The five global risks that are concerning according to him are global pandemic, financial collapse, world war, climate change and extreme poverty.

Factfulness in practice: Hans tells another wonderful story of how a tribal woman saved his life, when agitated villagers had surrounded him and wanted to kill him for doing research on their blood samples. He says she stepped up and convinced her fellow villagers with rational arguments how it was research that had helped them get vaccination against measles. This is what Hans gives as an example of factfulness in practice. He says we should teach our kids the following:

1) Majority of humanity is in the middle.

2) Socioeconomic position of one’s country in relation to others.

3) How this has improved over the years.

4) How life was really like in the past.

5) Things can be bad and getting better.

6) Cultural and religious stereotypes are useless.

7) How to consume news.

8) Beware of people trying to trick them with numbers.

9) Constantly update their knowledge and worldview.

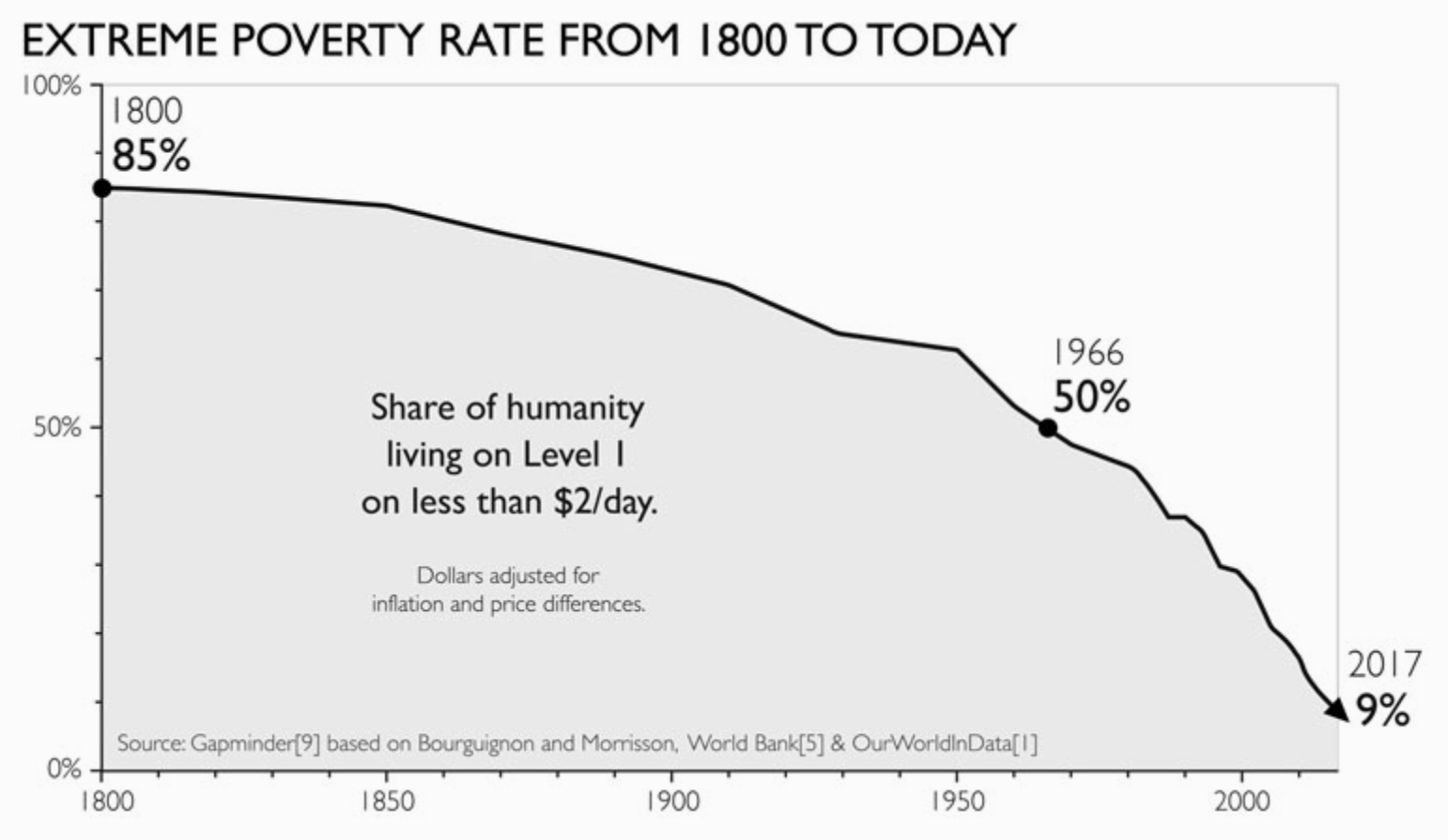

World is indeed getting better. Level 1 is where humanity started. In 1800, 85% of humanity lived in extreme poverty. This is down to 9% today.

One metric to know if countries are doing well or not, can be to see “how many children women have, and how many of them die”. The graph on the left shows the world in 1965, when majority of the world fell in the ‘developing’ box, but now in 2017, 85% of mankind are inside the ‘developed’ box, on the right. Only 13 countries remain in the developing box.

My thoughts:

Through this book, Hans Rosling wanted to leave a legacy of what he thought of as his life’s purpose of fighting widespread ignorance and promoting a fact-based worldview. He believed it will help us navigate through life better, just like an accurate GPS does. And that it would make life much more comfortable, less stressful and less dramatic. We can then start to see the world as it is. We do not have to do anything radical. We just have to keep doing more of what we are already doing. For eg. he says that we already know the solutions to ending extreme poverty: peace, schooling, universal basic health care, electricity, clean water, toilets, contraceptives and microcredits. There is no innovation needed here. It’s just about walking that last mile, providing these necessities of a decent life to the final billion, living in extreme poverty.

Conclusion:

Factfulness is an important book to read. It has certainly made me a possibilist, which is what Hans described himself as. Someone who does not just hope blindly, but hopes based on a fact-based worldview. This book has given me a strong foundation to understand the world around me. And I will hope to negate some of my instincts by applying these principles of factfulness in my life.